2025.10.11

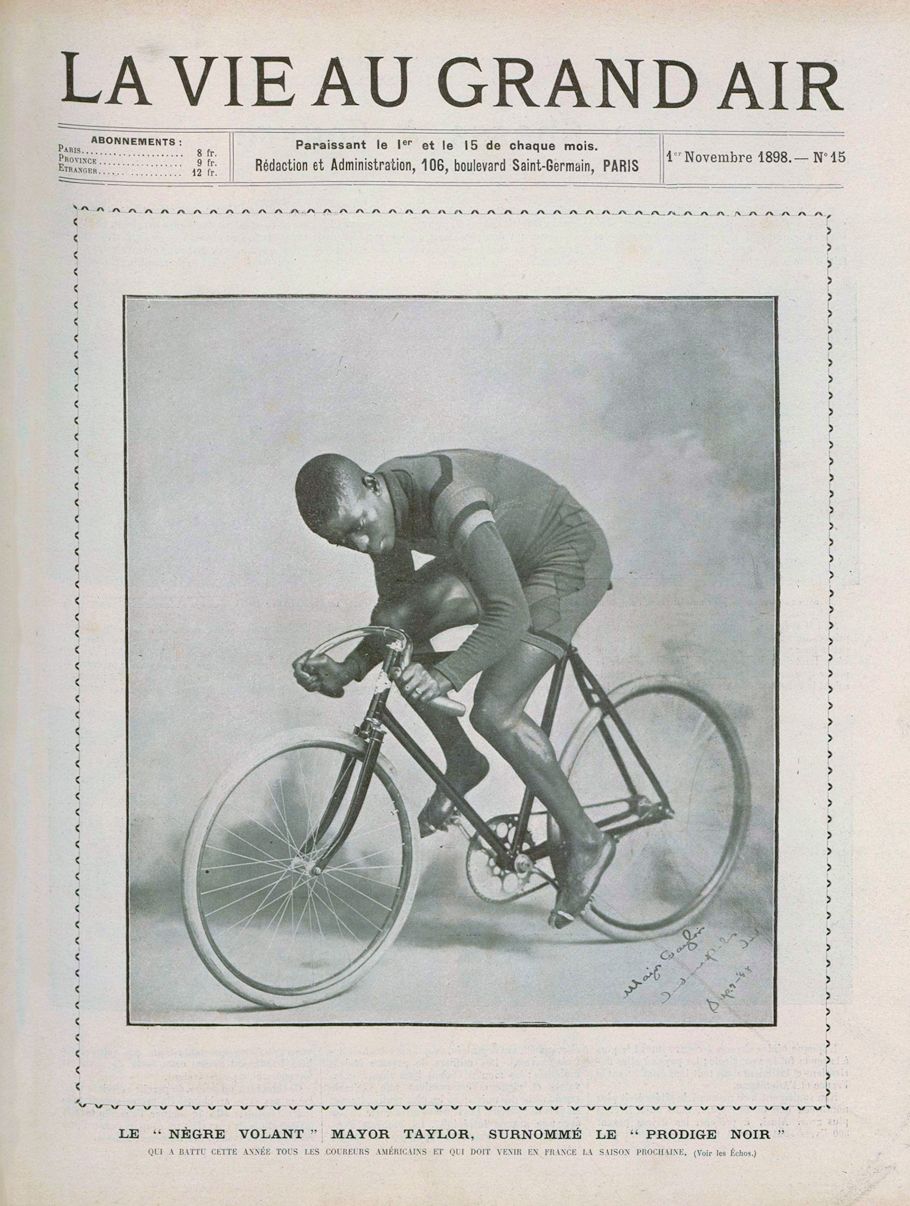

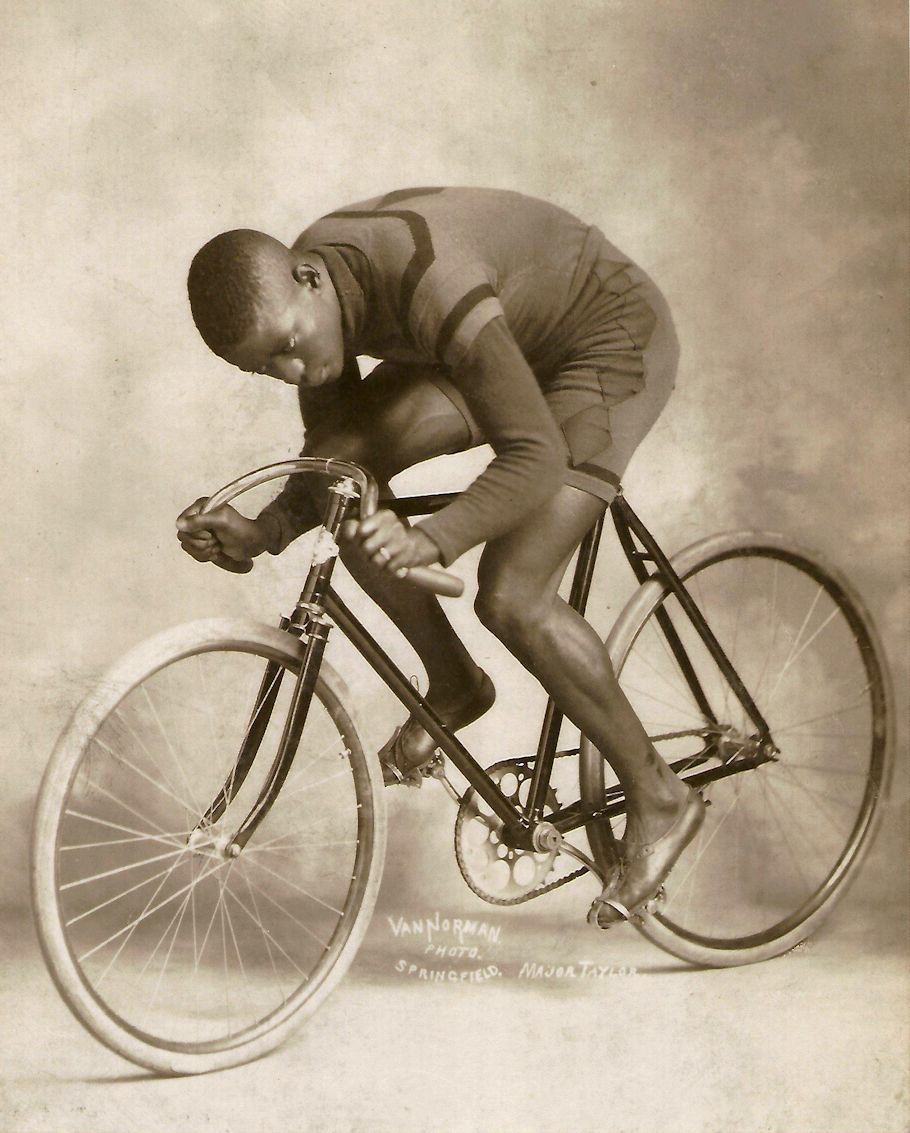

Marshall Walter "Major" Taylor on the front of the November 1, 1898, edition of the French sports magazine La Vie au grand air. Marcel Duchamp was 11 years old at the time.

During the first few years as a professional in the United States (1896 to 1900), Taylor aroused an intense hatred among some white riders as he began to challenge them for the best prizes--hefty purses of gold coins.

. . .

The editor of the New York Morning Telegraph, under the headline "The boycott against Taylor was too long delayed," was "pleased to see this emphatic assertion of the superiority of the Caucasian over the Ethiopian," although he wished that the white riders had boycotted Taylor before "the black whirlwind" had defeated them all. "It is, of course, a degradation for a white man to contest any points with a negro," he thought. "It is worse than that, and becomes an absolute grief and social disaster when a negro persistently wins in the competition."

Andrew Ritchie in David K. Wiggins, editor, Out of the Shadows: A Biographical History of African American Athletes (2006), pp. 25-7.

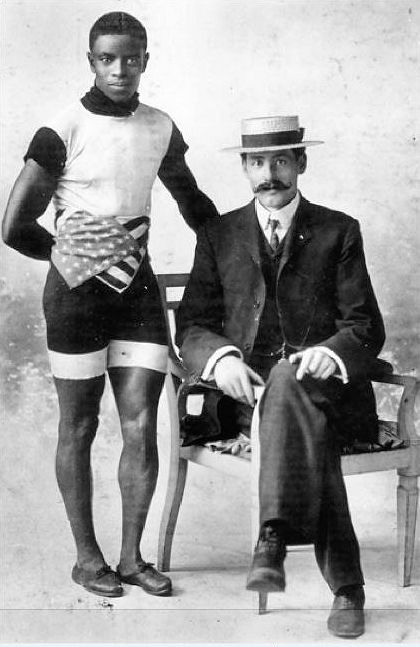

Marshall "Major" Taylor standing next to manager Victor Breyer in a 1901 photograph in Paris. This was at the height of Taylor's fame. Marcel Duchamp was 14 years old at the time.

In March 1901, when Taylor crossed the Atlantic for the first time, he was, according to the Worcester Spy, "the most universally admired passenger on the big ocean lines." In France, wrote Robert Coquelle (one of Taylor's French managers) in the cycling daily, Le Vélo, Taylor was awaited like the Messiah."

When he arrived in Paris, Taylor was a celebrity and was instantly transformed into an athletic superstar. The exhausting and triumphant tour of the summer of 1901 established him as black America's unofficial ambassador to Europe. His fame was consolidated and sustained by extensive coverage in the sporting and general interest press and by the publicity machine of the promoters. It was a press generated fame of a totally modern kind, with sport as the selling point, and a dramatic, and idiosyncratic personality to give it spice and meaning. The press met Taylor at Boulogne and followed him everywhere. In hundreds of daily reports, they wrote about what he looked like, how he dressed, what he did, what he said, what he ate, and how his training and racing were progressing. The sporting establishment, the newly prominent automobile manufacturers, and the Parisian aristocracy competed to entertain him. Letters from America addressed simply to "Major Taylor, Paris, France" arrived safely at his hotel. People followed him in the street just to touch him and paid entry fees to the tracks just to watch him train.

For probably the first time in modern sport history, a black athlete was marketed as a star and seen by thousands of people in a short space of time, in France, Germany, Italy, Austria, Denmark, and Holland.

Andrew Ritchie in David K. Wiggins, editor, Out of the Shadows: A Biographical History of African American Athletes (2006), pp. 30-1.

The Passion Considered as an Uphill Bicycle Race

Alfred Jarry

Translated by Roger Shattuck

Original title:

La passion considérée comme course de côte

Le Canard Sauvage, 11-17 avril 1903

Text source:

Selected Works of Alfred Jarry, edited by Roger Shattuck & Simon Watson Taylor, New York, Grove Press (1965, 1980).

Barabbas, slated to race, was scratched.

Pilate, the starter, pulling out his clepsydra or water clock, an operation which wet his hands unless he had merely spit on them. Pilate gave the send-off.

Jesus got away to a good start. In those days, according to the excellent sports commentator St Mathew, it was customary to flagellate the sprinters at the start the way a coachman whips his horses. The whip both stimulates and gives a hygienic massage. Jesus, then, got off in good form, but he had a flat right away. A bed of thorns punctured the whole circumference of his front tyre.

Today in the shop windows of bicycle dealers you see a reproduction of this veritable crown of thorns as an ad for puncture-proof tyres. But Jesus’s was an ordinary singletube racing tyre.

The two thieves, obviously in cahoots and therefore 'thick as thieves', took the lead.

It is not true that there were any nails. The three objects usually shown in the ads belong to a rapid-change tyre tool called the

'Jiffy'.

We had better begin by telling about the spills; but before that the machine itself must be described.

The bicycle frame in use today is of relatively recent invention. It appeared around 1890. Previous to that time the body of the machine was constructed of two tubes soldered together at right angles. It was generally called the right-angle or cross bicycle. Jesus, after his puncture, climbed the slope on foot, carrying on his shoulder the bike frame, or, if you will, the cross.

Contemporary engravings reproduce this scene from photographs. But it appears that the sport of cycling, as a result of the well-known accident which put a grievous end to the Passion race and which was brought up to date almost on its anniversary by the similar accident of Count Zborowski on the Turbie slope--the sport of cycling was for a time prohibited by state ordinance. That explains why the illustrated magazines, in reproducing this celebrated scene, show bicycles of a rather imaginary design. They confuse the machine's cross frame with that other cross, the straight handlebar. They represent Jesus with his hands spread on the handlebars, and it is worth mentioning in this connection that Jesus rode lying flat on his back in order to reduce his air resistance.

Note also that the frame or cross was made of wood, just as wheels are to this day.

A few people have insinuated falsely that Jesus's machine was a draisienne, an unlikely mount for a hill-climbing contest. According to the old cyclophile hagiographers, St. Briget, St. Gregory of Tours, and St. Irene, the cross was equipped with a device which they name suppendaneum. There is no need to be a great scholar to translate this as 'pedal'.

Lipsius, Justinian, Bosius, and Erycius Puteanus describe another accessory which one still finds, according to Cornelius Curtius in 1643, on Japanese crosses; a protuberance of leather or wood on the shaft which the rider sits astride--manifestly the seat or

saddle.

This general description, furthermore, suits the definition of a bicycle current among the Chinese: "A little mule which is led by the ears and urged along by showering it with kicks."

We shall abridge the story of the race itself, for it has been narrated in detail by specialized works and illustrated by sculpture and painting visible in monuments built to house such art.

There are fourteen turns in the difficult Golgotha course. Jesus took his first spill at the third turn. His mother, who was in the

stands, became alarmed.

His excellent trainer, Simon the Cyrenian, who but for the thorn accident would have been riding out in front to cut the wind, carried the machine.

Jesus, though carrying nothing, perspired heavily. It is not certain whether a female spectator wiped his brown, but we know that Veronica, a girl reporter, got a good shot of him with her Kodak.

The second spill came at the seventh turn on some slippery pavement. Jesus went down for the third time at the eleventh turn, skidding on a rail.

The Israelite deminondaines waved their handkerchiefs at the eighth.

The deplorable accident familiar to us all took place at the twelfth turn. Jesus was in a dead heat at the time with the thieves.

We know that he continued the race airborne, but that is another story.

www.patakosmos.com

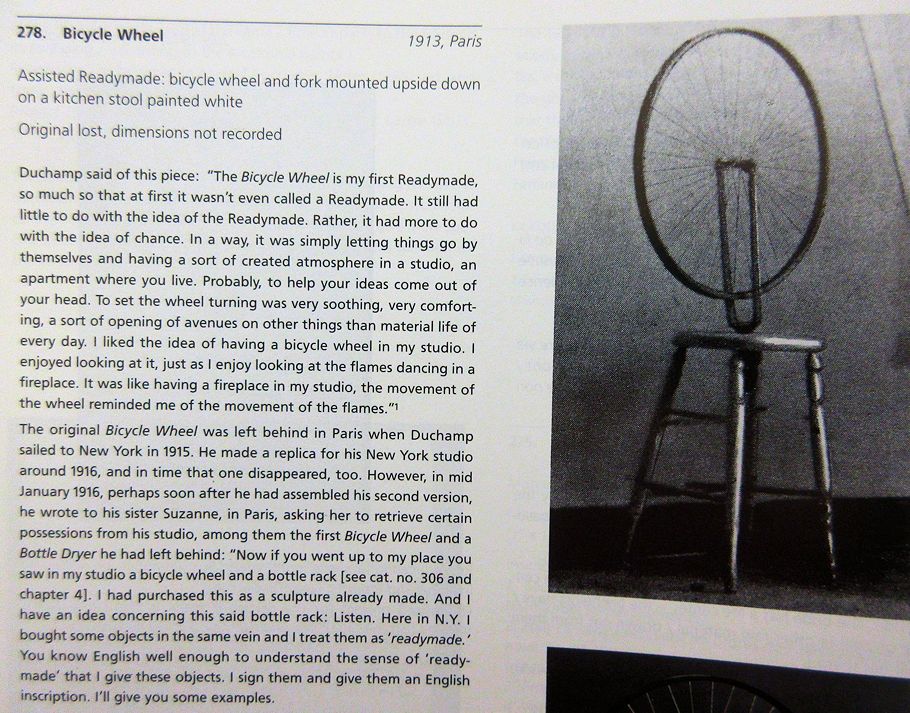

Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (2000), p. 588.

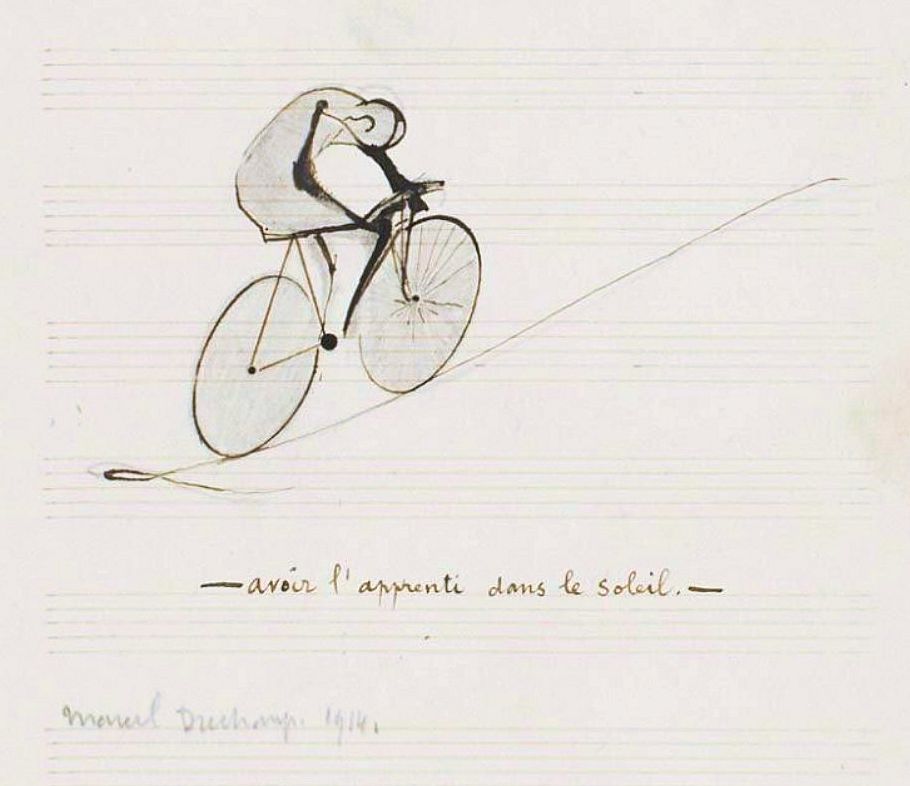

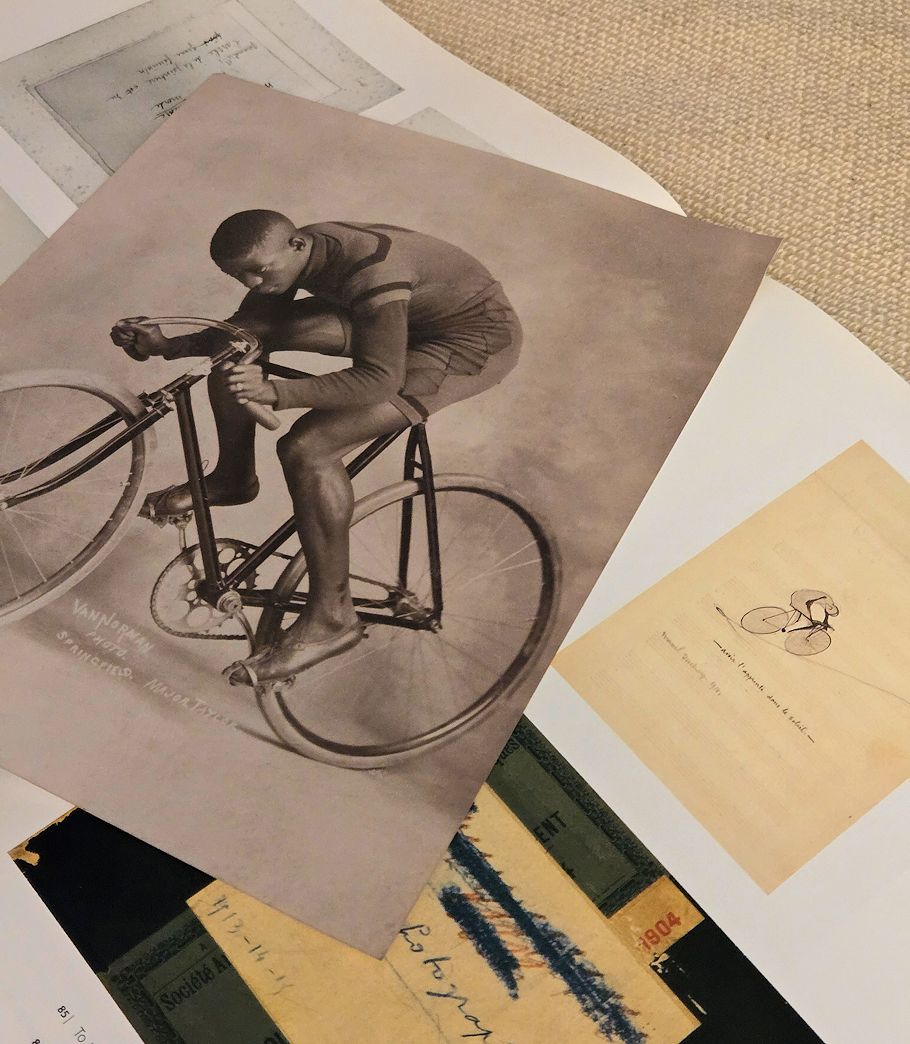

Marcel Duchamp, To Have the Apprentice in the Sun, January 1914, Rouen.

The image [To Have the Apprentice in the Sun] was most probably suggested by an Alfred Jarry prose poem, "The Passion as an Uphill Bicycle Race," which had been reprinted a few years before. Duchamp's drawing is one of elements of The Box of 1914, 1913-14, where, like all the other contents, it is reproduced photographically. The original drawing was presented to Louise and Walter Arensberg around 1921.

Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (2000), p. 598.

Reproduction of a historic photograph of Marshall "Major" Taylor circa 1898, purchased by Stephen Lauf from Brewerytown Paperboy 2025.07.27 (coincidentally the day before the 138th anniversary of Marcel Duchamp's birth).

2025.07.27: 451.rhawn.gallery . . . wonders if this is the first time these two images have been photographed together.

So far, I have found no reference connecting Marshall "Major" Taylor with the work of either Alfred Jarry or Marcel Duchamp, yet, at this point, the connection appears explicitly obvious. Moreover, the now obvious connection begs the question, why has this connection never been noted before? And ultimately, do Jarry's and Duchamp's covert references to Marshall "Major" Taylor have anything to do with race and/or racism, or were Jarry and/or Duchamp simply covetous of Taylor's unprecedented modern fame?

Stephen Lauf, Duchamp After Unbekannt (2025.10.11), p. 0006s.

|